Which maybe is a long way of saying…

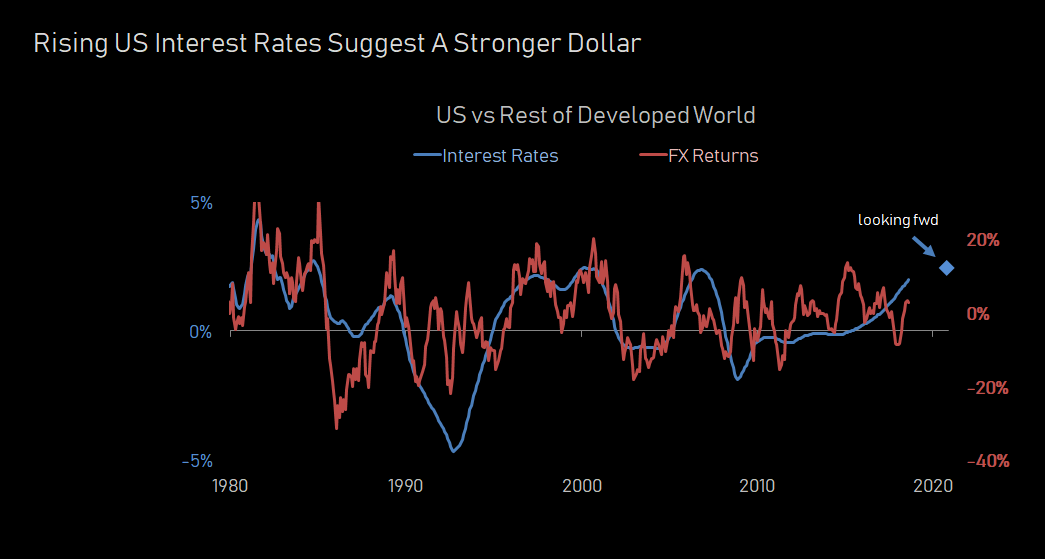

Yes the dollar could fall 30%, but we think it has to rally at least another 10-20% before it does.

Which maybe is a long way of saying…

Yes the dollar could fall 30%, but we think it has to rally at least another 10-20% before it does.

Some of us live in a world of dollars.

As opposed to pounds, or yen, or deutschemarks, we experience the everyday prices for goods and services in units of dollars.

Everything from our morning coffee, to rent, to our retirement savings is priced in terms of “how many dollar bills is this thing worth?”

Most of us don’t spend time thinking about the fact that a dollar bill is itself a commodity. It’s just one of those helpful abstractions that comes from thinking that a dollar bill is ‘money.’

This abstraction tends to unravel when, like this week, famous investors make public predictions that

“The Federal Reserve…will have to print more money to make up for the deficit, have to monetize more and…You easily could have a 30 percent depreciation in the dollar”

At Black Snow, while we don’t disagree with Ray’s logic that:

Fed Easing > Lower Interest Rates -> Debt Monetization -> Weaker Dollar

We do disagree with the timeline and path that the dollar may take.

Given that the Fed is currently tightening (and most other major central banks are easing), the first order pressure on the dollar aught be to strengthen. It’s hard to see the dollar selling off that much in a world where a bank account in New York gets you 2% (and rising) more than a bank account in London, Tokyo or Frankfurt.

Further, when you think about what the world would need to look like to get the Fed to switch from tightening:

Everything is fine -> Raise Interest Rates -> Shrink the Fed Balance Sheet

To easing:

Everything is doomed -> Lower Interest Rates -> Buy Assets/Print Money

You need a mechanism by which global demand contracts and prompts a change in policy.

What’s the most likely cause of a contraction in global demand?

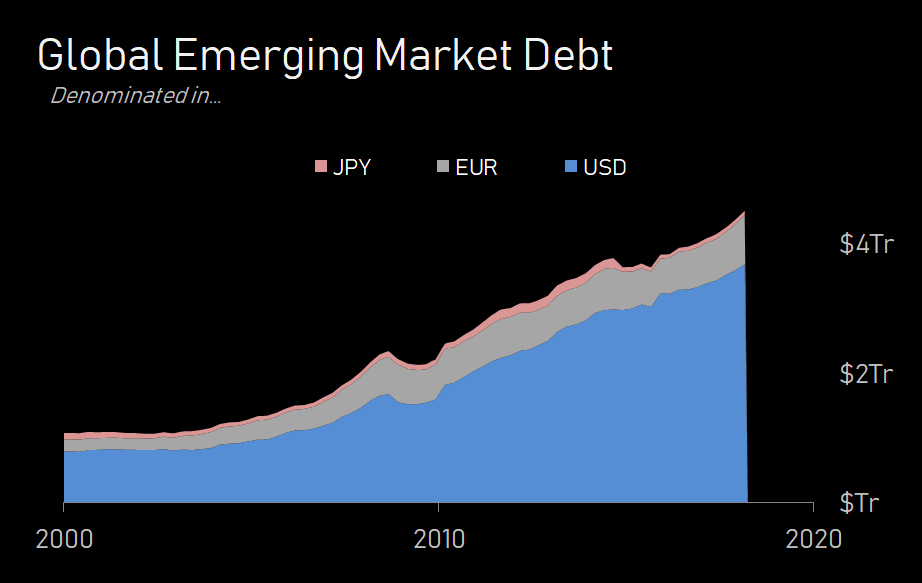

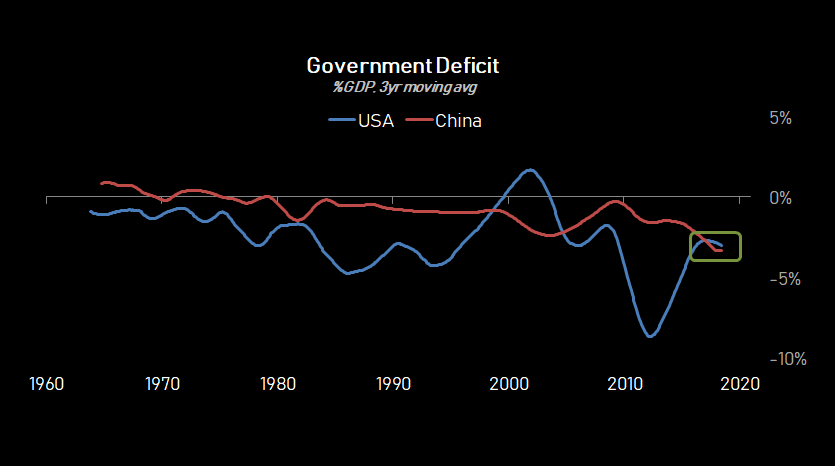

Yes, deficits in the US are large and unsustainable.

But it’s not like the US is the only one that needs to get it’s fiscal house in order.

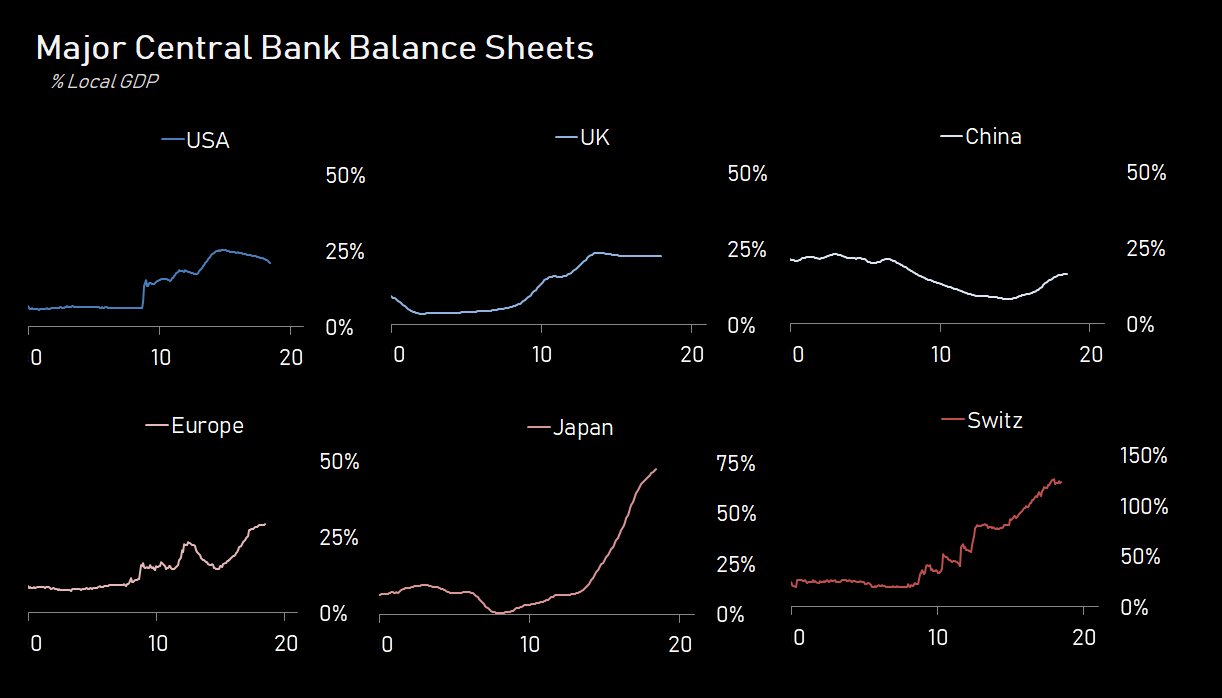

Yes, in the next downturn, the Fed will likely return to printing money.

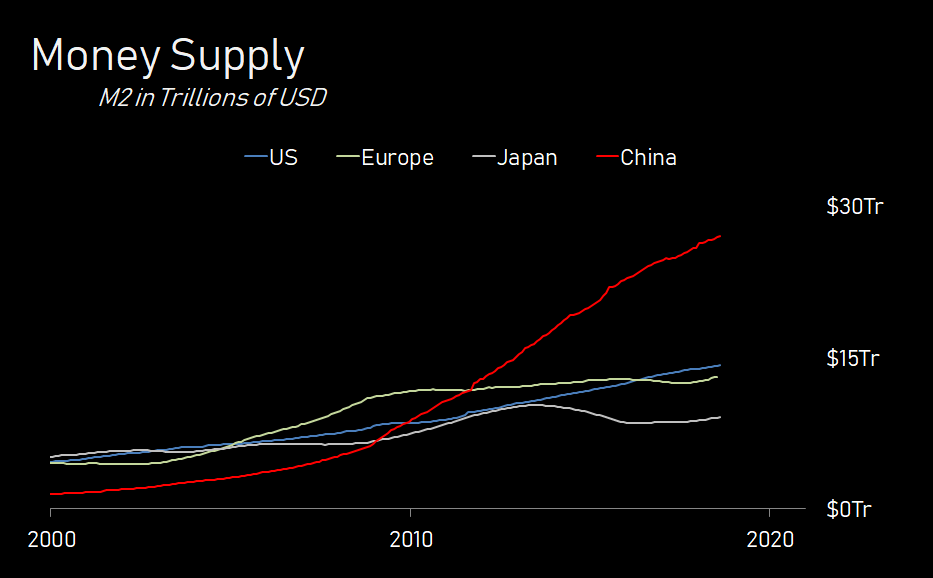

But when put in context of money printing in the rest of the world, it’s not like the US is the one that stands out.

*Central Bank Balance Sheets for Japan and China are ex-foreign currency reserves

Further, if you are worried about an unsustainable expansion in money, the US doesn’t seem like a prime candidate for worry.

So yes, we think it likely that in the next downturn, major central banks will print money to buy assets.

In the meantime, our view is that the relatively tight monetary policy by the Fed will lead to an appreciation in the dollar against most major currencies. That this stronger dollar will lead to the next downturn in the global credit cycle, as tightening in the reserve currency traditionally has.

Thus, we remain long dollars.

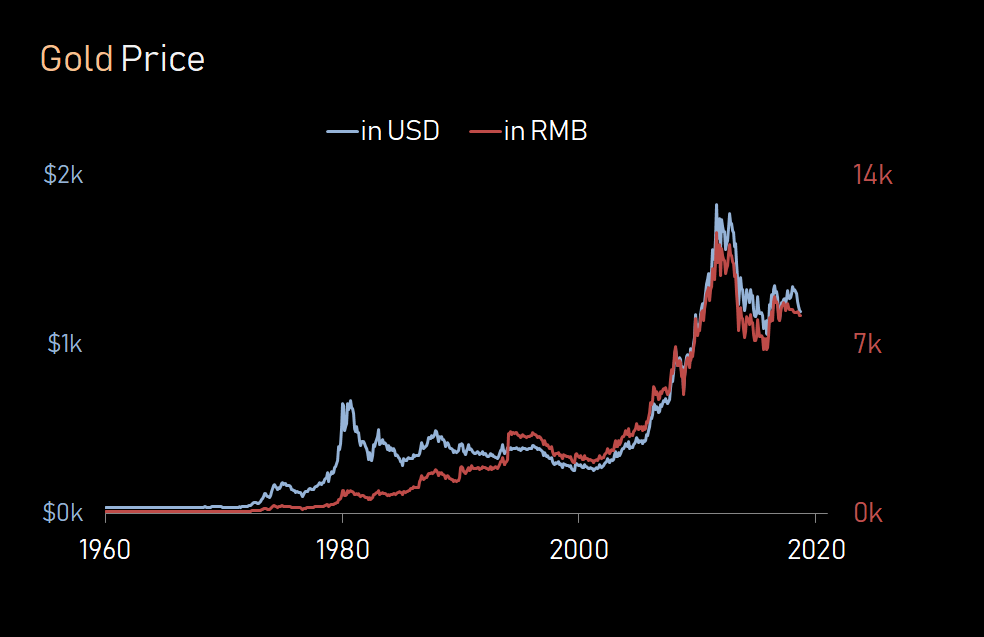

This downturn will likely see a broad depreciation of all paper currencies relative to real assets, as policymakers inject liquidity to local credit markets by printing money.

At that point, it will be less a story about dollar weakness in particular, and more a story of ‘which one’, ‘how much’ and ‘against what’….

We recommend gold (denominated in RMB) as a natural hedge for this eventually outcome.

At Black Snow, we believe it pays not only to study history, but to form mental models of the systems that guide history. That the creation and refinement of these models not only help us understand the world, but help us trade markets.

This post is about the high-level system we see guiding the allocation of resources in and across three distinct domains of human affairs. It is the system that defines how capital, in its broadest sense, evolves and defines our day to day life.

We call it #theMachine.

The Machine has three parts.

Each part representing a form of capital that guides human affairs in a particular domain. Each with existing internal feedback loops. Each with defined (but constantly evolving) ways of interacting with the other domains.

Cultural capital can can be thought of as the ability to mobilize financial and technological resources purely through personal or institutional clout.

As culture is the domain of purely human affairs, cultural capital represents standing and power amongst humans.

The ability of a politician's tweet to move markets, or of a celebrity endorsement to change opinions is a manifestation of the cultural capital those individuals posses. Though this clout is recorded not in any balance sheet or hard drive, it exists nonetheless.

We take a broad definition of culture here, one that contains both the explicit (politics) and implicit (class) hierarchical structure that we as social apes spend our days in.

Simply put, technological capital is the ability to do more, with less.

It can be thought of as the ability of an individual, organization or society, to design, implement and maintain systems.

Some of those systems, create, store and transport physical goods and services, be they a barrel of oil or a iPhone.

Some of those systems deal with non-physical objects, be they streaming movies or search results.

In some sense less, tech capital isn't as immediately apparent than the other two forms of capital, as its primary impact is to the reduce the financial and cultural cost of doing business.

Financial capital is the domain of money, wealth, and obligation. Of assets and liabilities. Equity and Debt. Inflows and Outflows.

Finance can be thought of as the great book of accounts in the sky. That which records who owe's whom what, and the prevailing market prices by which those debits and credits were exchanged.

While this system has evolved significantly since Hummurabi's slab was used to make the first recorded insurance contracts, it's relationship with the other two forms of capital remains relatively constant.

Financial capital is the ability to make change in that great distributed ledger, and in doing so, mobilize change in the domains of culture (humans) and technology (systems).

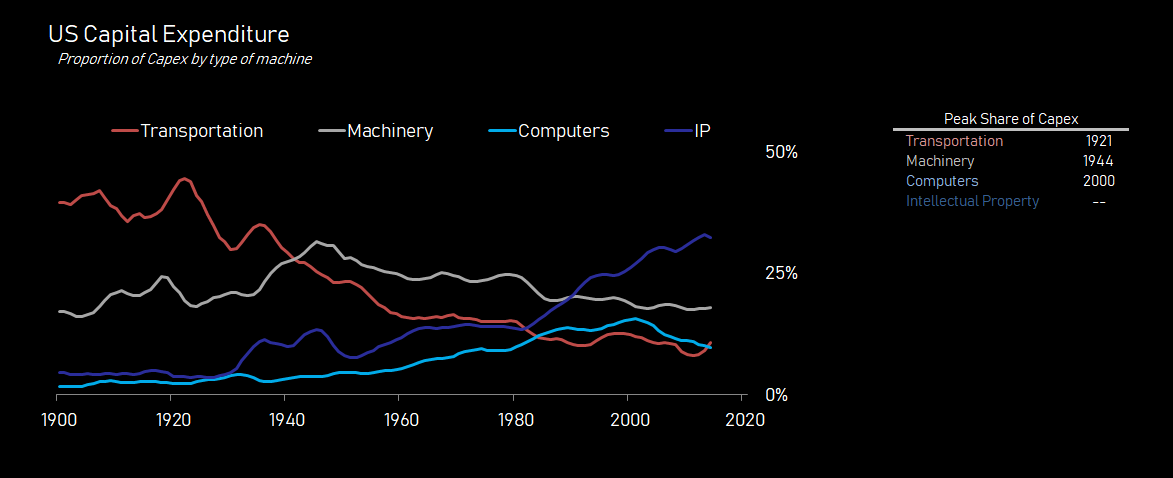

The goal of this post was to lay out the three forms of capital as we see them.

In subsequent posts, we will go a level deeper, and walk through how the three forms of capital function, interact, and evolve.

In this work, we'll attempt to provide the logic (backed up with data) behind the three charts in this post.

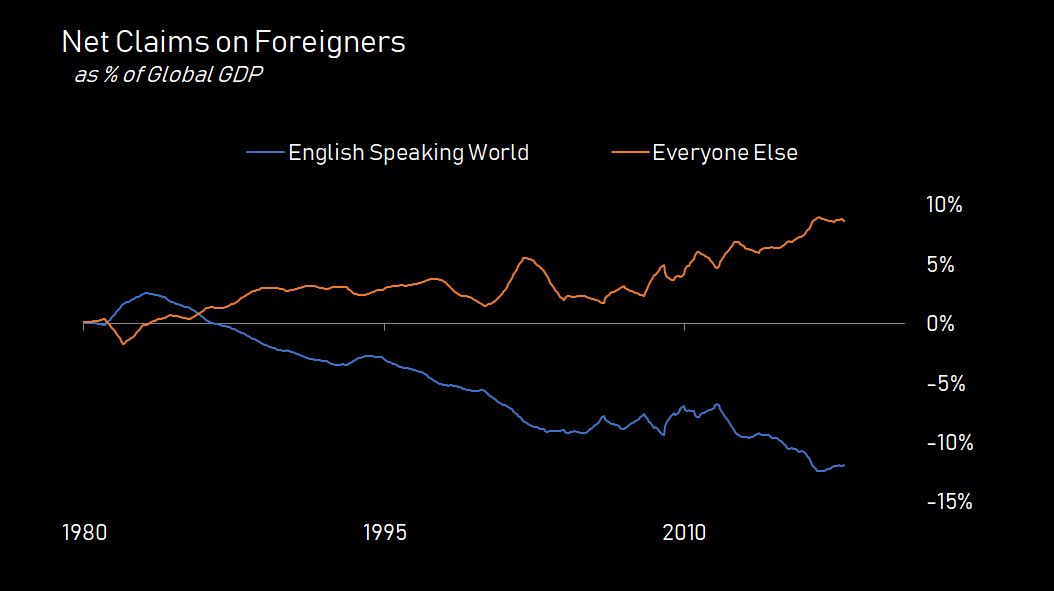

For example, how can the US (and by association the UK and it's former colonies) be the source of so much of the world's technological and cultural capital, whilst simultaneously owing everyone else so much money?

Once you start to see the world in these terms, it becomes hard to stop.

Someone I respect a great deal taught me that setting goals was a pretty important part of the process of getting what you want out of life.

Since seeing this, I have become rather obsessed with thinking about goals. I found that much of what could be called regret came down to sloppy thinking on my part about what my goals actually were, and what a good process towards reaching those goals looked like.

The power of this heuristic then extended to knowing and understanding the goals of others. It has reached the point where pretty much my first conversation with any potential business associate is a frank discussion about our mutual goals. I find it becomes much easier to build flexibility into a relationship when all parties have mutually consistent goals, because everyone knows everyone is essentially rowing in the same direction.

Anyway, the throat-clearing here is to provide some context for why this first post is about goals.

The goals of this blog are simple:

1. Use publishing on this blog as a forcing function to structure some of our thinking about markets and investing.

2. Socialize that thinking such that others can engage with that thinking, by asking questions, pushing back, and holding us accountable.

3. Through that process, increase the rate at which we learn about the world and, in doing so, create value for our investors.

With those goals in mind, we plan to prioritize transparency and the asking of questions in this blog vs coming up with high-confidence, specific answers to specific questions.

We accept that we might be wrong, that at times we will be wrong, and we look forward to figuring out which is which, with you.